Wikipedista:Chmee2/Pískoviště

| Ceres | |

|---|---|

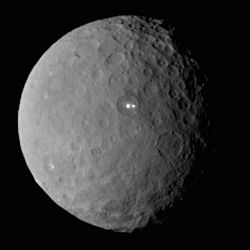

Ceres zachycený sondou Dawn 19. února 2015. | |

| Identifikátory | |

| Typ | planetka |

| Označení | (1) Ceres |

| Předběžné označení | A899 OF 1943 XB |

| Katalogové číslo | 1 |

| Objeveno | |

| Datum | 1. ledna 1801 |

| Místo | Osservatorio Reale di Palermo |

| Objevitel | G. Piazzi |

| Elementy dráhy (Ekvinokcium J2000,0) | |

| Epocha | 2005-08-18 00:00:00,0 UTC 2453600,5 JD |

| Velká poloosa | 413 784 635 km 2,7660 au |

| Výstřednost | 0,0800 |

| Perihel | 380 676 070 km 2,5447 au |

| Afel | 446 893 199 km 2,9873 au |

| Perioda (oběžná doba) | 1680,26 d (4,6003 a) |

| Střední denní pohyb | 0,2143°/den |

| Sklon dráhy | |

| - k ekliptice | 10,5860° |

| Délka vzestupného uzlu | 80,4097° |

| Argument šířky perihelu | 73,3924° |

| Střední anomálie | 86,9544° |

| Průchod perihelem | 2004-07-08 03:42:16,9 UTC 2453194,6544 JD |

| Fyzikální charakteristiky | |

| Absolutní hvězdná velikost | 3,387 |

| Rovníkový průměr | 952 (975 × 909) km |

| Hmotnost | ~ 9,5×1020 kg |

| Průměrná hustota | 2,077 ± 0,036 g/cm³ |

| Gravitační parametr | 63,2 km³/s² |

| Gravitace na rovníku | 0,27 m/s² (0,028 G) |

| Úniková rychlost | 350 km/s |

| Perioda rotace | 9,075 h 0,3781 d |

| Sklon rotační osy | 4º ± 5° |

| Albedo | 0,1132 |

| Spektrální třída | G (C) |

Šablona:Infobox planet (1) Ceres je prvním objeveným a současně svým rovníkovým průměrem 975 km největším objektem obíhajícím mezi drahami Marsu a Jupiteru, tedy v oblasti hlavního pásu planetek. Svoji hmotností představuje asi 30 % hmotnosti pásu asteroidů mezi Marsem a Jupiterem. První půlstoletí po objevu byl považován za planetu, později za planetku. Na základě rezoluce XXVI. Generálního zasedání Mezinárodní astronomické unie (IAU) v srpnu 2006 v Praze, která definovala pojem planeta, byl zařazen do nové kategorie těles sluneční soustavy, mezi tzv. trpasličí planety.

Ceres (Šablona:IPAc-en;[1] minor-planet designation: 1 Ceres) is the largest object in the asteroid belt that lies between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter. Its diameter is approximately 945 kilometer (587 mil),[2] making it the largest of the minor planets within the orbit of Neptune. The 33rd-largest known body in the Solar System, it is the only dwarf planet within the orbit of Neptune.[a][3] Composed of rock and ice, Ceres is estimated to compose approximately one third of the mass of the entire asteroid belt. Ceres is the only object in the asteroid belt known to be rounded by its own gravity (though detailed analysis was required to exclude 4 Vesta). From Earth, the apparent magnitude of Ceres ranges from 6.7 to 9.3, and hence even at its brightest it is too dim to be seen with the naked eye except under extremely dark skies.

Ceres was the first asteroid to be discovered (by Giuseppe Piazzi at Palermo on 1. ledna 1801). It was originally considered a planet, but was reclassified as an asteroid in the 1850s after many other objects in similar orbits were discovered.

Ceres appears to be differentiated into a rocky core and an icy mantle, and may have a remnant internal ocean of liquid water under the layer of ice.[4][5] The surface is probably a mixture of water ice and various hydrated minerals such as carbonates and clay. In January 2014, emissions of water vapor were detected from several regions of Ceres.[6] This was unexpected because large bodies in the asteroid belt typically do not emit vapor, a hallmark of comets.

The robotic NASA spacecraft Dawn entered orbit around Ceres on 6 March 2015.[7][8][9] Pictures with a resolution previously unattained were taken during imaging sessions starting in January 2015 as Dawn approached Ceres, showing a cratered surface. Two distinct bright spots (or high-albedo features) inside a crater (different from the bright spots observed in earlier Hubble images[10]) were seen in a 19 February 2015 image, leading to speculation about a possible cryovolcanic origin[11][12][13] or outgassing.[14] On 3 March 2015, a NASA spokesperson said the spots are consistent with highly reflective materials containing ice or salts, but that cryovolcanism is unlikely.[15] However, on 2 September 2016, NASA scientists released a paper in Science that claimed that a massive ice volcano called Ahuna Mons is the strongest evidence yet for the existence of these mysterious ice volcanoes.[16][17] On 11 May 2015, NASA released a higher-resolution image showing that, instead of one or two spots, there are actually several.[18] On 9 December 2015, NASA scientists reported that the bright spots on Ceres may be related to a type of salt, particularly a form of brine containing magnesium sulfate hexahydrite (MgSO4·6H2O); the spots were also found to be associated with ammonia-rich clays.[19] In June 2016, near-infrared spectra of these bright areas were found to be consistent with a large amount of sodium carbonate (Šablona:Chem), implying that recent geologic activity was probably involved in the creation of the bright spots.[20][21][22]

In October 2015, NASA released a true color portrait of Ceres made by Dawn.[23] In February 2017, organics were reported to have been detected on Ceres in Ernutet crater (see image).[24]

Historie editovat

Objevení editovat

V roce 1772 Johann Elert Bode poprvé naznačil, že by mezi oběžnými drahami Marsu a Jupiteru mohla existovat doposud neobjevená planeta.[25] Bode vycházel z Titius-Bodeova pravidla, dnes zneplatněné hypotézy poprvé formulované v roce 1766. Bode si totiž povšiml pravidelnosti v hodnotách průměrné vzdálenosti tehdy známých planet sluneční soustavy a na základě této zdánlivé pravidelnosti předpokládal existenci doposud neznámé planety. V podstatě šlo o to, že každá tehdy známá planeta byla přibližně dvakrát vzdálenější od Slunce, než planeta předchozí; výjimku představovala mezera mezi oběžnou drahou Marsu a Jupiteru.[25][26] Vznikl tak předpoklad, že by se v této oblasti měla nacházet doposud neznámá planeta s velkou poloosou dráhy okolo 2,8 astronomických jednotek (AU) od Slunce.[26] Když se povedlo Williamu Herschelovi objevit v roce 1781 planetu Uran přibližně ve vzdálenosti předpovězenou tímto pravidlem, víra v jeho správnost narostla.[25] Řada astronomů se tak dala do jejího hledání. Jedním z nich byl i dvorní astronom ve městě Gotha, baron Franz Xaver von Zach, který podporován Bodem, začal v roce 1787 s jejím hledáním. Rozumně se omezil na oblast nebeské sféry poblíže ekliptiky. Za tím účelem si vytvořil vlastní katalog hvězd blízkých ekliptice, ale i tak bylo jeho snažení marné. Na podzim 1799 navštívil astronomy v Celle, Brémách a v Lilienthalu, s nimiž o tomto problému diskutoval. Došli k závěru, že takový úkol nemůže zvládnout jeden astronom. Proto se 21. září 1800[25][26] sešli v Lilienthalu von Zach, J. H. Schröter, H. W. M. Olbers, C. L. Harding, F. A. von Ende a J. Gildemeister. Protože na schůzce dospěli k závěru, že ani šest zkušených pozorovatelů není dostatečný počet, rozhodli se přizvat další evropské astronomy. Rozdělili proto oblast zvířetníku na 24 stejných úseků po 15° a vymezili tyto úseky na oblast 7° až 8° na sever a na jih od ekliptiky. O přidělení oblastí rozhodoval los. Tak vznikla první mezinárodní astronomická kampaň v historii. Její účastníci se nazvali „nebeskou policií“ („Himmelspolizei“).

Jedním z přizvaných astronomů byl i italský katolický kněz a profesor matematiky Giuseppe Piazzi z Palerma na Sicílii, který sice nebyl zkušeným astronomem, ale díky podpoře tehdejšího neapolského krále Ferdinanda IV. vybudoval v létech 1780 až 1791 ve věži královského zámku astronomickou observatoř. V té době to byla nejjižnější hvězdárna v celé Evropě. V roce 1789 ji vybavil výkonným čočkovým dalekohledem s objektivem o průměru 7,5 cm, pětistopým vertikálním a třístopým azimutálním kruhem s velmi přesným odečítáním souřadnic, který zhotovil anglický mechanik Jesse Ramsden. Toto zařízení patřilo ke špičkovým astrometrickým přístrojům té doby. Hlavním cílem Piazziho však nebylo hledání nové planety, ale sestavení co nejpřesnějšího katalogu hvězd. Na tomto úkolu pracoval též 1. ledna 1801. Při hledání hvězdy Mayer 87 podle Wollastonova katalogu (ve skutečnosti se jednalo o hvězdu Lacaille 87, z toho důvodu poloha u Wollastona nesouhlasila s údaji v Mayerově katalogu a proto to Piazzi kontroloval) spatřil dosud nepopsaný objekt hvězdné velikosti 8m. Piazzi tak objevil Ceres.[27][28] Když dalšího dne zjistil, že se objekt mezi hvězdami posunul, věnoval mu bližší pozornost. Dne 24. ledna téhož roku rozeslal kolegům dopis o objevu, kde objekt opatrně nazval kometou.[29] Svému kolegovi B. Orianimu do Milána např. napsal:

Pozoroval jsem 1. ledna poblíž ramena Býka hvězdu osmé velikosti, která se dalšího večera, tedy 2., posunula o 3′ 30″ přibližně k severu a o 4′ přibližně ke znamení Berana … Já bych tu hvězdu označil jako kometu, avšak nevykazuje žádnou mlhovinu a pak její pohyb je tak pomalý a pravidelný, že mi spíše připadá na mysl, že by to mohlo být něco lepšího než nějaká kometa.[25] Je to jen domněnka a to mi velice brání ji zveřejnit…

Pozorování pokračovalo až do 11. února 1801, kdy se objekt přiblížil ke Slunci natolik, že již nebyl pozorovatelný. Celkem jej Piazzi sledoval po dvacet čtyři nocí. Vyjma Orianimu se o svých pozorováních svěřil i Johannu Bodemu.[30] V dubnu 1801 pak zaslal kompletní zprávu o svých pozorováních Orianimu, Bodemu a Jérômu Lalandeovi. Zpráva byla následně zveřejněna v září 1801 v časopise Monatliche Correspondenz.[29]

Přestože byl Piazzi matematik, neměl k dispozici vhodnou výpočetní metodu, aby z tak krátkého úseku dráhy stanovil dostatečně přesně elementy dráhy nového tělesa. Svými výpočty pouze zjistil, že se nepohybuje po parabole, což se tehdy předpokládalo o kometách, ale spíše po kružnici.

Problém výpočtu parametrů však vyřešil geniální německý vědec C. F. Gauss, který vypracoval v létě roku 1801 matematický postup, umožňující stanovit elementy dráhy z menšího počtu pozorování, tzv. metodu nejmenších čtverců. Díky tomu mohl planetku von Zach 7. prosince 1801 znovu objevit.

Prakticky až do poloviny 19. století byla ještě považována za planetu a dostala dokonce i grafický symbol (viz vlevo). Ani objev dalších planetek na tom nic nezměnil. Teprve v 50. letech 19. století, kdy objevů planetek kvapem přibývalo, začala být spolu s ostatními podobnými tělesy považována za pouhou planetku. Na počátku Piazzi velikost nového tělesa značně přecenil; odhadoval, že jeho průměr je srovnatelný s průměrem Země. Naproti tomu anglický astronom William Herschel již v květnu 1802 po objevu druhé planetky (2) Pallas Heinrichem Wilhelmem Olbersem předpokládal, že se jedná o malá tělesa a navrhl je pojmenovat asteroidy, tedy hvězdám podobné.

V roce 2006 byl spolu s (134340) Plutem a transneptunickým tělesem (136199) Eris zařazen do nově vytvořené kategorie trpasličích planet. I nadále je však veden v oficiálním katalogu malých těles sluneční soustavy pod katalogovým číslem 1.

By this time, the apparent position of Ceres had changed (mostly due to Earth's orbital motion), and was too close to the Sun's glare for other astronomers to confirm Piazzi's observations. Toward the end of the year, Ceres should have been visible again, but after such a long time it was difficult to predict its exact position. To recover Ceres, Carl Friedrich Gauss, then 24 years old, developed an efficient method of orbit determination.[29] In only a few weeks, he predicted the path of Ceres and sent his results to von Zach. On 31 December 1801, von Zach and Heinrich W. M. Olbers found Ceres near the predicted position and thus recovered it.[29]

The early observers were only able to calculate the size of Ceres to within an order of magnitude. Herschel underestimated its diameter as 260 km in 1802, whereas in 1811 Johann Hieronymus Schröter overestimated it as 2,613 km.[31][32]

Pojmenování editovat

Piazzi původně navrhoval pojmenovat toto objevené těleso jako Cerere Ferdinandea dle římské bohyně plodnosti a úrody Cerery a sicilského krále Ferdinanda I.[25][29] Přízvisko "Ferdinandea" ale nebylo přijatelné pro jiné tehdejší státy, takže se od jeho používání upustilo. Ceres byla po krátký čas v oblasti dnešního Německa označovaná jako Hera.[33] V řečtině je naproti tomu Cerera označována jako Demeter (Δήμητρα), což je řecký ekvivalent římské Cerery.

The old astronomical symbol of Ceres is a sickle, Šablona:Angbr ( ),[34] similar to Venus' symbol Šablona:Angbr but with a break in the circle. It has a variant Šablona:Angbr, reversed under the influence of the initial letter 'C' of 'Ceres'. These were later replaced with the generic asteroid symbol of a numbered disk, Šablona:Angbr.[29][35]

Cer, prvek ze skupiny vzácných zemin objevený v roce 1803 byl pojmenován na počest Cerery. V ten samý rok byl po Cereře pojmenován i další prvek, nicméně když byl název ceru uznán, objevitel prvku svůj návrh změnil a prvek pojmenoval palladium na počest druhé objevené planetky 2 Pallas.[36]

Klasifikace editovat

Zařazení Cerery se v průběhu let změnilo více než jednou a bylo předmětem sporů. Johann Elert Bode věřil, že Cerera je chybějící planeta, jejíž existenci navrhoval mezi oběžnou drahou Marsu a Jupiteru ve vzdálenosti 419 miliónů km (2,8 AU) od Slunce.[25] Cereře byl udělen symbol využívaný pro označení planet a po následující polovinu století byla společně s planetky 2 Pallas, 3 Juno a 4 Vesta vedena v astronomických knihách a tabulkách jako planeta.[25][29][37]

Jak byly v okolí Cerery postupně pozorovány další objekty, astronomové si uvědomili, že Ceres představuje první pozorovaný objekt z nové skupiny nebeských těles.[25] V roce 1802 s objevením 2 Pallas zavedl William Herschel pro tyto objekty termín asteroid znamenající „podobající se hvězdám“.[37] Ceres jako první objevené těleso z této skupiny dostal dle později zavedené identifikace planetek číslo 1. Od 60. let 19. století bylo všeobecně přijímáno, že se asteroidy, kam byla Ceres zařazena, významně liší od planet. Nicméně s tím, že definice planety nebyla v tehdejší době přesně definována.[37]

The 2006 debate surrounding Pluto and what constitutes a planet led to Ceres being considered for reclassification as a planet.[38][39] A proposal before the International Astronomical Union for the definition of a planet would have defined a planet as "a celestial body that (a) has sufficient mass for its self-gravity to overcome rigid-body forces so that it assumes a hydrostatic equilibrium (nearly round) shape, and (b) is in orbit around a star, and is neither a star nor a satellite of a planet".[40] Had this resolution been adopted, it would have made Ceres the fifth planet in order from the Sun.[41] This never happened, however, and on 24 August 2006 a modified definition was adopted, carrying the additional requirement that a planet must have "cleared the neighborhood around its orbit". By this definition, Ceres is not a planet because it does not dominate its orbit, sharing it as it does with the thousands of other asteroids in the asteroid belt and constituting only about a third of the mass of the belt. Bodies that met the first proposed definition but not the second, such as Ceres, were instead classified as dwarf planets.

Ceres je největším tělesem v Pásu asteroidů.[42] It is sometimes assumed that Ceres has been reclassified as a dwarf planet, and that it is therefore no longer considered an asteroid. For example, a news update at Space.com spoke of "Pallas, the largest asteroid, and Ceres, the dwarf planet formerly classified as an asteroid",[43] whereas an IAU question-and-answer posting states, "Ceres is (or now we can say it was) the largest asteroid", though it then speaks of "other asteroids" crossing Ceres' path and otherwise implies that Ceres is still considered an asteroid.[44] The Minor Planet Center notes that such bodies may have dual designations.[45] The 2006 IAU decision that classified Ceres as a dwarf planet never addressed whether it is or is not an asteroid. Indeed, the IAU has never defined the word 'asteroid' at all, having preferred the term 'minor planet' until 2006, and preferring the terms 'small Solar System body' and 'dwarf planet' after 2006. Lang (2011) comments "the [IAU has] added a new designation to Ceres, classifying it as a dwarf planet. ... By [its] definition, Eris, Haumea, Makemake and Pluto, as well as the largest asteroid, 1 Ceres, are all dwarf planets", and describes it elsewhere as "the dwarf planet–asteroid 1 Ceres".[46] NASA continues to refer to Ceres as an asteroid,[47] as do various academic textbooks.[48][49]

Oběžná dráha editovat

| Element type |

a (in AU) |

e | i | Period (in days) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proper[50] | 2.7671 | 0.116198 | 9.647435 | 1,681.60 |

| Osculating[51] (Epoch 23 July 2010 ) |

2.7653 | 0.079138 | 10.586821 | 1,679.66 |

| Difference | 0.0018 | 0.03706 | 0.939386 | 1.94 |

Ceres follows an orbit between Mars and Jupiter, within the asteroid belt, with a period of 4.6 Earth years.[51] The orbit is moderately inclined (i = 10.6° compared to 7° for Mercury and 17° for Pluto) and moderately eccentric (e = 0.08 compared to 0.09 for Mars).[51]

The diagram illustrates the orbits of Ceres (blue) and several planets (white and gray). The segments of orbits below the ecliptic are plotted in darker colors, and the orange plus sign is the Sun's location. The top left diagram is a polar view that shows the location of Ceres in the gap between Mars and Jupiter. The top right is a close-up demonstrating the locations of the perihelia (q) and aphelia (Q) of Ceres and Mars. In this diagram (but not in general), the perihelion of Mars is on the opposite side of the Sun from those of Ceres and several of the large main-belt asteroids, including 2 Pallas and 10 Hygiea. The bottom diagram is a side view showing the inclination of the orbit of Ceres compared to the orbits of Mars and Jupiter.

Ceres was once thought to be a member of an asteroid family.[52] The asteroids of this family share similar proper orbital elements, which may indicate a common origin through an asteroid collision some time in the past. Ceres was later found to have spectral properties different from other members of the family, which is now called the Gefion family after the next-lowest-numbered family member, 1272 Gefion.[52] Ceres appears to be merely an interloper in the Gefion family, coincidentally having similar orbital elements but not a common origin.[53]

Rezonance editovat

Ceres is in a near-1:1 mean-motion orbital resonance with Pallas (their proper orbital periods differ by 0.2%).[54] However, a true resonance between the two would be unlikely; due to their small masses relative to their large separations, such relationships among asteroids are very rare.[55] Nevertheless, Ceres is able to capture other asteroids into temporary 1:1 resonant orbital relationships (making them temporary trojans) for periods up to 2 million years or more; fifty such objects have been identified.[56]

Transits of planets from Ceres editovat

Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars can all appear to cross the Sun, or transit it, from a vantage point on Ceres. The most common transits are those of Mercury, which usually happen every few years, most recently in 2006 and 2010. The most recent transit of Venus was in 1953, and the next will be in 2051; the corresponding dates are 1814 and 2081 for transits of Earth, and 767 and 2684 for transits of Mars.[57]

Rotace a sklon osy editovat

The rotation period of Ceres (the Cererian day) is 9 hours and 4 minutes.[58] It has an axial tilt of 4°. This is small enough for Ceres's polar regions to contain permanently shadowed craters that are expected to act as cold traps and accumulate water ice over time, similar to the situation on the Moon and Mercury. About 0.14% of water molecules released from the surface are expected to end up in the traps, hopping an average of 3 times before escaping or being trapped.[59]

Geology editovat

Spektroskopický průzkum ukázal, že povrchová vrstva obsahuje značné množství uhlíku a pravděpodobně i organických látek a podobá se do jisté míry svým chemickým složením uhlíkatým chondritům a že je tedy málo přetvořeným původním materiálem, ze kterého těleso akrecí vzniklo. Bylo proto zařazeno po spektrální stránce do kategorie G (v hrubší klasifikaci do třídy C).

Předpokládá se, že při formování tohoto objektu došlo k částečné diferenciaci jeho nitra, způsobené především teplem vznikajícím při radioaktivním rozpadu 26Al. Původní materiál, který obsahoval značné množství vodního ledu roztál, a těžší silikátové horniny klesly ke středu, kde vytvořily kamenné jádro. Chladnoucí obal kapalné vody s příměsí lehčích, převážně uhlíkatých látek vytvořil plášť, jehož tloušťka se odhaduje na 60 až 120 km. Nejvyšší vrstva, odhadem 10 km silná, se však nikdy plně neroztavila a tvoří kůru planetky, se složením blízkým původnímu materiálu. Kůra byla pouze částečně přetvořena dopady menších těles. To potvrzují i radiolokační pozorování podle nichž je povrch Cerery pokryt vrstvou regolitu.

Z průměrné hustoty se dá vyvodit, že voda na Cereře tvoří asi 17 až 27 % její hmotnosti, což přestavuje v průměru asi 2×108 km3 vody, tedy přibližně pětkrát více, než je celkové množství vody na zemském povrchu. Přítomnost vody v povrchových vrstvách byla nepřímo spektroskopicky prokázána měřením ultrafialového spektra astronomickou družicí IUE, která objevila čáry hydroxylu OH, svědčícího o stále se obnovující velice řídké atmosféře vodní páry, unikající z povrchu tělesa.

Cerera neprodělala v průběhu své existence žádnou kolizi s větším tělesem, která by významněji zasáhlo do jejího geologického vývoje. Nejvyšší horou na povrchu Cerery je 4 kilometry vysoká Ahuna Mons.

Ceres has a mass of 9,39×1020 kg as determined from the Dawn spacecraft.[60] With this mass Ceres composes approximately a third of the estimated total 3.0 ± 0.221×10{{{2}}} kg mass of the asteroid belt,[61] which is in turn approximately 4% of the mass of the Moon. Ceres is massive enough to give it a nearly spherical, equilibrium shape.[62] Among Solar System bodies, Ceres is intermediate in size between the smaller Vesta and the larger Tethys. Its surface area is approximately the same as the land area of India or Argentina.[63]

Povrch editovat

Složení povrchu Cerery se značně shoduje s asteroidy typu C, což je označení pro asteroidy bohaté na uhlík.[42] Nicméně některé rozdíly ve složení jsou přítomny. Všudypřítomné útvary viditelné v infračervném spektru světla odpovídají hydratovaným minerálům, což napovídá o přítomnosti značného množství vody uvnitř Cerery. Na povrchu se vyskytují také železem bohaté jílové minerály (jako například cronstedtit a karbonáty, konkrétně dolomit a siderit), což jsou běžné minerály v uhlíkatých chondritech.[42] The spectral features of carbonates and clay minerals are usually absent in the spectra of other C-type asteroids.[42] Sometimes Ceres is classified as a G-type asteroid.[64]

Ceres' surface is relatively warm. The maximum temperature with the Sun overhead was estimated from measurements to be 235 K (approximately −38 °C, −36 °F) on 5 May 1991.[65] Ice is unstable at this temperature. Material left behind by the sublimation of surface ice could explain the dark surface of Ceres compared to the icy moons of the outer Solar System.

(bw; true-color; IR) of Ceres.

Studies by the Hubble Space Telescope reveal that graphite, sulfur, and sulfur dioxide are present on Ceres's surface. The former is evidently the result of space weathering on Ceres's older surfaces; the latter two are volatile under Cerean conditions and would be expected to either escape quickly or settle in cold traps, and are evidently associated with areas with recent geological activity.[66]

Pozorování před příletem sondy Dawn editovat

Prior to the Dawn mission, only a few surface features had been unambiguously detected on Ceres. High-resolution ultraviolet Hubble Space Telescope images taken in 1995 showed a dark spot on its surface, which was nicknamed "Piazzi" in honor of the discoverer of Ceres.[64] This was thought to be a crater. Later near-infrared images with a higher resolution taken over a whole rotation with the Keck telescope using adaptive optics showed several bright and dark features moving with Ceres' rotation.[67][68] Two dark features had circular shapes and were presumed to be craters; one of them was observed to have a bright central region, whereas another was identified as the "Piazzi" feature.[67][68] Visible-light Hubble Space Telescope images of a full rotation taken in 2003 and 2004 showed eleven recognizable surface features, the natures of which were then undetermined.[69][70] One of these features corresponds to the "Piazzi" feature observed earlier.[69]

These last observations indicated that the north pole of Ceres pointed in the direction of right ascension 19 h 24 min (291°), declination +59°, in the constellation Draco, resulting in an axial tilt of approximately 3°.[69][62] Dawn later determined that the north polar axis actually points at right ascension 19 h 25 m 40.3 s (291.418°), declination +66° 45' 50" (about 1.5 degrees from Delta Draconis), which means an axial tilt of 4°.[2]

Průzkum sondou Dawn editovat

Dawn revealed that Ceres has a heavily cratered surface; nevertheless, Ceres does not have as many large craters as expected, likely due to past geological processes.[71][72] An unexpectedly large number of Cererian craters have central pits, perhaps due to cryovolcanic processes, and many have central peaks.[73] Ceres has one prominent mountain, Ahuna Mons; this peak appears to be a cryovolcano and has few craters, suggesting a maximum age of no more than a few hundred million years.[74][75] A later computer simulation has suggested that there were originally other cryovolcanoes on Ceres that are now unrecognisable due to viscous relaxation.[76] Several bright spots have been observed by Dawn, the brightest spot ("Spot 5") located in the middle of an 80-kilometer (50 mi) crater called Occator.[77] From images taken of Ceres on 4 May 2015, the secondary bright spot was revealed to actually be a group of scattered bright areas, possibly as many as ten. These bright features have an albedo of approximately 40%[78] that are caused by a substance on the surface, possibly ice or salts, reflecting sunlight.[79][80] A haze periodically appears above Spot 5, the best known bright spot, supporting the hypothesis that some sort of outgassing or sublimating ice formed the bright spots.[80][81] In March 2016, Dawn found definitive evidence of water molecules on the surface of Ceres at Oxo crater.[82][83] JPL states: "This water could be bound up in minerals or, alternatively, it could take the form of ice."

On 9 December 2015, NASA scientists reported that the bright spots on Ceres may be related to a type of salt, particularly a form of brine containing magnesium sulfate hexahydrite (MgSO4·6H2O); the spots were also found to be associated with ammonia-rich clays.[19] Another team thinks the salts are sodium carbonate.[21][22]

|

"Spot 1" (top row) ("cooler" than surroundings); "Spot 5" (bottom) ("similar in temperature" as surroundings) (April 2015) |

Vnitřní stavba editovat

Zaoblenost Cerery je ve shodě s představou, že Cerera je vnitřně diferenciovaným tělesem s kamenitým jádrem, nad kterým se rozkládá ledový plášť.[62] Plášť má mocnost okolo 100 kilometrů (představuje tak okolo 23 až 28 % hmotnosti Cerery a okolo 50 % jejího objemu)[85] a pravděpodobně obsahuje okolo 200 miliónů kubických kilometrů vodního ledu, což představuje větší množství než je sladké vody na povrchu Země.[86] This result is supported by the observations made by the Keck telescope in 2002 and by evolutionary modeling.[4][67] Also, some characteristics of its surface and history (such as its distance from the Sun, which weakened solar radiation enough to allow some fairly low-freezing-point components to be incorporated during its formation), point to the presence of volatile materials in the interior of Ceres.[67] It has been suggested that a remnant layer of liquid water may have survived to the present under a layer of ice.[4][5]

Shape and gravity field measurements by Dawn confirm Ceres is a body in hydrostatic equilibrium with partial differentiation[87][88] and isostatic compensation, with a mean moment of inertia of 0.37 (which is similar to that of Callisto at ~0.36).[89] The densities of the core and outer layer are estimated to be 2.46–2.90 and 1.68–1.95 g/cm3, with the latter being about 70–190 km thick. Only partial dehydration of the core is expected. The high density of the outer layer (relative to water ice) reflects its enrichment in silicates and salts.[89] Ceres is the smallest object confirmed to be in hydrostatic equilibrium, being 600 km smaller and less than half the mass of Saturn's moon Rhea, the next smallest such object.[90] Modeling has suggested Ceres could have a small metallic core from partial differentiation of its rocky fraction.[91]

Atmosféra editovat

There are indications that Ceres has a tenuous water vapor atmosphere outgassing from water ice on the surface.[92][93][94]

Surface water ice is unstable at distances less than 5 AU from the Sun,[95] so it is expected to sublime if it is exposed directly to solar radiation. Water ice can migrate from the deep layers of Ceres to the surface, but escapes in a very short time. As a result, it is difficult to detect water vaporization. Water escaping from polar regions of Ceres was possibly observed in the early 1990s but this has not been unambiguously demonstrated. It may be possible to detect escaping water from the surroundings of a fresh impact crater or from cracks in the subsurface layers of Ceres.[67] Ultraviolet observations by the IUE spacecraft detected statistically significant amounts of hydroxide ions near Ceres' north pole, which is a product of water vapor dissociation by ultraviolet solar radiation.[92]

In early 2014, using data from the Herschel Space Observatory, it was discovered that there are several localized (not more than 60 km in diameter) mid-latitude sources of water vapor on Ceres, which each give off approximately 1026 molecules (or 3 kg) of water per second.[96][97][pozn. 1] Two potential source regions, designated Piazzi (123°E, 21°N) and Region A (231°E, 23°N), have been visualized in the near infrared as dark areas (Region A also has a bright center) by the W. M. Keck Observatory. Possible mechanisms for the vapor release are sublimation from approximately 0.6 km2 of exposed surface ice, or cryovolcanic eruptions resulting from radiogenic internal heat[96] or from pressurization of a subsurface ocean due to growth of an overlying layer of ice.[5] Surface sublimation would be expected to be lower when Ceres is farther from the Sun in its orbit, whereas internally powered emissions should not be affected by its orbital position. The limited data available was more consistent with cometary-style sublimation;[96] however, subsequent evidence from Dawn strongly suggests ongoing geologic activity could be at least partially responsible.[100][101]

Studies using Dawn's gamma ray and neutron detector (GRaND) reveal that Ceres is accelerating electrons from the solar wind regularly; although there are several possibilities as to what is causing this, the most accepted is that these electrons are being accelerated by collisions between the solar wind and a tenuous water vapor exosphere.[102]

In 2017, Dawn confirmed that Ceres has a transient atmosphere that appears to be linked to solar activity. Ice on Ceres can sublimate when energetic particles from the Sun hit exposed ice within craters.[103]

Původ a vývoj editovat

Ceres is possibly a surviving protoplanet (planetary embryo), which formed 4.57 billion years ago in the asteroid belt.[4] Although the majority of inner Solar System protoplanets (including all lunar- to Mars-sized bodies) either merged with other protoplanets to form terrestrial planets or were ejected from the Solar System by Jupiter,[104] Ceres is thought to have survived relatively intact.[4] An alternative theory proposes that Ceres formed in the Kuiper belt and later migrated to the asteroid belt.[105] The discovery of ammonia salts in Occator crater supports an origin in the outer Solar System.[106] Another possible protoplanet, Vesta, is less than half the size of Ceres; it suffered a major impact after solidifying, losing ~1% of its mass.[107]

The geological evolution of Ceres was dependent on the heat sources available during and after its formation: friction from planetesimal accretion, and decay of various radionuclides (possibly including short-lived isotopes such as the cosmogenic nuclide aluminium-26). These are thought to have been sufficient to allow Ceres to differentiate into a rocky core and icy mantle soon after its formation.[69][4] This process may have caused resurfacing by water volcanism and tectonics, erasing older geological features.[4] Ceres's relatively warm surface temperature implies that any of the resulting ice on its surface would have gradually sublimated, leaving behind various hydrated minerals like clay minerals and carbonates.[42]

Today, Ceres has become considerably less geologically active, with a surface sculpted chiefly by impacts;[69] nevertheless, evidence from Dawn reveals that internal processes have continued to sculpt Ceres's surface to a significant extent, in stark contrast to Vesta[108] and of previous expectations that Ceres would have become geologically dead early in its history due to its small size.[4][109] The presence of significant amounts of water ice in its composition[62] and evidence of recent geological resurfacing, raises the possibility that Ceres has a layer of liquid water in its interior.[4][109] This hypothetical layer is often called an ocean.[42] If such a layer of liquid water exists, it is hypothesized to be located between the rocky core and ice mantle like that of the theorized ocean on Europa.[4] The existence of an ocean is more likely if solutes (i.e. salts), ammonia, sulfuric acid or other antifreeze compounds are dissolved in the water.[4]

Případná obyvatelnost editovat

Although not as actively discussed as a potential home for microbial extraterrestrial life as Mars, Titan, Europa or Enceladus, there is evidence that Ceres' icy mantle was once a watery subterranean ocean, and that has led to speculations that life could have existed there,[110][111][112][113] and that hypothesized ejecta bearing microorganisms could have come from Ceres to Earth.[114][115]

Pozorování a průzkum editovat

Pozorování editovat

When Ceres has an opposition near the perihelion, it can reach a visual magnitude of +6.7.[117] This is generally regarded as too dim to be seen with the naked eye, but under exceptional viewing conditions a very sharp-sighted person may be able to see it. The only other asteroids that can reach a similarly bright magnitude are 4 Vesta, and, during rare oppositions near perihelion, 2 Pallas and 7 Iris.[118] At a conjunction Ceres has a magnitude of around +9.3, which corresponds to the faintest objects visible with 10×50 binoculars. It can thus be seen with binoculars whenever it is above the horizon of a fully dark sky.

Some notable observations and milestones for Ceres include:

- 1984 November 13: An occultation of a star by Ceres observed in Mexico, Florida and across the Caribbean.[119]

- 1995 June 25: Ultraviolet Hubble Space Telescope images with 50-kilometer resolution.[64][120]

- 2002: Infrared images with 30-km resolution taken with the Keck telescope using adaptive optics.[68]

- 2003 and 2004: Visible light images with 30-km resolution (the best prior to the Dawn mission) taken using Hubble.[69][70]

- 2012 December 22: Ceres occulted the star TYC 1865-00446-1 over parts of Japan, Russia, and China.[121] Ceres' brightness was magnitude 6.9 and the star, 12.2.[121]

- 2014: Ceres was found to have an atmosphere with water vapor, confirmed by the Herschel space telescope.[122]

- 2015: The NASA Dawn spacecraft approached and orbited Ceres, sending detailed images and scientific data back to Earth.

Exploration editovat

In 1981, a proposal for an asteroid mission was submitted to the European Space Agency (ESA). Named the Asteroidal Gravity Optical and Radar Analysis (AGORA), this spacecraft was to launch some time in 1990–1994 and perform two flybys of large asteroids. The preferred target for this mission was Vesta. AGORA would reach the asteroid belt either by a gravitational slingshot trajectory past Mars or by means of a small ion engine. However, the proposal was refused by ESA. A joint NASA–ESA asteroid mission was then drawn up for a Multiple Asteroid Orbiter with Solar Electric Propulsion (MAOSEP), with one of the mission profiles including an orbit of Vesta. NASA indicated they were not interested in an asteroid mission. Instead, ESA set up a technological study of a spacecraft with an ion drive. Other missions to the asteroid belt were proposed in the 1980s by France, Germany, Italy, and the United States, but none were approved.[123] Exploration of Ceres by fly-by and impacting penetrator was the second main target of the second plan of the multiaimed Soviet Vesta mission, developed in cooperation with European countries for realisation in 1991–1994 but canceled due to the Soviet Union disbanding.

In the early 1990s, NASA initiated the Discovery Program, which was intended to be a series of low-cost scientific missions. In 1996, the program's study team recommended as a high priority a mission to explore the asteroid belt using a spacecraft with an ion engine. Funding for this program remained problematic for several years, but by 2004 the Dawn vehicle had passed its critical design review.[124]

It was launched on 27 September 2007, as the space mission to make the first visits to both Vesta and Ceres. On 3 May 2011, Dawn acquired its first targeting image 1.2 million kilometers from Vesta.[125] After orbiting Vesta for 13 months, Dawn used its ion engine to depart for Ceres, with gravitational capture occurring on 6 March 2015[126] at a separation of 61,000 km,[127] four months prior to the New Horizons flyby of Pluto.

Dawn's mission profile calls for it to study Ceres from a series of circular polar orbits at successively lower altitudes. It entered its first observational orbit ("RC3") around Ceres at an altitude of 13,500 km on 23 April 2015, staying for only approximately one orbit (fifteen days).[9][128] The spacecraft will subsequently reduce its orbital distance to 4,400 km for its second observational orbit ("survey") for three weeks,[129] then down to 1,470 km ("HAMO;" high altitude mapping orbit) for two months[130] and then down to its final orbit at 375 km ("LAMO;" low altitude mapping orbit) for at least three months.[131] The spacecraft instrumentation includes a framing camera, a visual and infrared spectrometer, and a gamma-ray and neutron detector. These instruments will examine Ceres' shape and elemental composition.[132] On 13 January 2015, Dawn took the first images of Ceres at near-Hubble resolution, revealing impact craters and a small high-albedo spot on the surface, near the same location as that observed previously. Additional imaging sessions, at increasingly better resolution took place on 25 January, 4, 12, 19, and 25 February, 1 March, and 10 and 15 April.[133]

DawnŠablona:'s arrival in a stable orbit around Ceres was delayed after, close to reaching Ceres, it was hit by a cosmic ray, making it take another, longer route around Ceres in back, instead of a direct spiral towards it.[134]

The Chinese Space Agency is designing a sample retrieval mission from Ceres that would take place during the 2020s.[135]

Map of quadrangles editovat

The following imagemap of the dwarf planet Ceres is divided into 15 quadrangles. They are named after the first craters whose names the IAU approved in July 2015.[136] The map image(s) were taken by the Dawn space probe. Šablona:Ceres Quads - By Name

Notes editovat

- ↑ Ceres [online]. Random House, Inc. [cit. 2007-09-26]. Dostupné v archivu pořízeném z originálu dne 5 October 2011.

- ↑ a b Chybná citace: Chyba v tagu

<ref>; citaci označenépresentationnení určen žádný text - ↑ STANKIEWICZ, Rick. A visit to the asteroid belt. Peterborough Examiner. 20 February 2015. Dostupné online [cit. 29 May 2015].

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k MCCORD, T. B.; SOTIN, C. Ceres: Evolution and current state. Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets. 21 May 2005, s. E05009. Dostupné online [cit. 7 March 2015]. DOI 10.1029/2004JE002244. Bibcode 2005JGRE..110.5009M.

- ↑ a b c (March 2015) "The Potential for Volcanism on Ceres due to Crustal Thickening and Pressurization of a Subsurface Ocean". 46th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference: 2831. Retrieved on 1 March 2015.

- ↑ NASA Science News: Water Detected on Dwarf Planet Ceres , by Production editor: Dr. Tony Phillips | Credit: Science@NASA (22 January 2014)

- ↑ LANDAU, Elizabeth; BROWN, Dwayne. NASA Spacecraft Becomes First to Orbit a Dwarf Planet [online]. 6 March 2015 [cit. 2015-03-06]. Dostupné online.

- ↑ Dawn Spacecraft Begins Approach to Dwarf Planet Ceres [online]. [cit. 2014-12-29]. Dostupné online.

- ↑ a b RAYMAN, Marc. Dawn Journal: Ceres Orbit Insertion! [online]. Planetary Society, 6 March 2015 [cit. 2015-03-06]. Dostupné online.

- ↑ PLAIT, Phil. The Bright Spots of Ceres Spin Into View [online]. 11 May 2015 [cit. 2015-05-30]. Dostupné online.

- ↑ O'NEILL, I. Ceres' Mystery Bright Dots May Have Volcanic Origin [online]. Discovery Communications, 25 February 2015 [cit. 2015-03-01]. Dostupné online.

- ↑ LANDAU, E. 'Bright Spot' on Ceres Has Dimmer Companion [online]. Jet Propulsion Laboratory, 25 February 2015 [cit. 2015-02-25]. Dostupné v archivu pořízeném z originálu dne 26 February 2015.

- ↑ LAKDAWALLA, E. At last, Ceres is a geological world [online]. Planetary Society, 26 February 2015 [cit. 2015-02-26]. Dostupné online.

- ↑ LPSC 2015: First results from Dawn at Ceres: provisional place names and possible plumes [online]. Dostupné online.

- ↑ ATKINSON, Nancy. Bright Spots on Ceres Likely Ice, Not Cryovolcanoes [online]. 3 March 2015 [cit. 2015-03-04]. Dostupné online.

- ↑ INSIDER, ALI SUNDERMIER, Business. NASA just found an ice volcano on Ceres that's half the size of Everest [online]. [cit. 2016-09-05]. Dostupné online.

- ↑ RUESCH, O.; PLATZ, T.; SCHENK, P.; MCFADDEN, L. A.; CASTILLO-ROGEZ, J. C.; QUICK, L. C.; BYRNE, S. Cryovolcanism on Ceres. Science. 2016-09-02, s. aaf4286. Dostupné online. ISSN 0036-8075. DOI 10.1126/science.aaf4286. Bibcode 2016Sci...353.4286R. (anglicky)

- ↑ Ceres RC3 Animation [online]. 11 May 2015 [cit. 2015-07-31]. Dostupné online.

- ↑ a b LANDAU, Elizabeth. New Clues to Ceres' Bright Spots and Origins [online]. 9 December 2015 [cit. 2015-12-10]. Dostupné online.

- ↑ LANDAU, Elizabeth; GREICIUS, Tony. Recent Hydrothermal Activity May Explain Ceres' Brightest Area. NASA. 29 June 2016. Dostupné online [cit. 30 June 2016].

- ↑ a b LEWIN, Sarah. Mistaken Identity: Ceres Mysterious Bright Spots Aren't Epsom Salt After All. Space.com. 29 June 2016. Dostupné online [cit. 2016-06-30].

- ↑ a b DE SANCTIS, M. C.; ET AL. Bright carbonate deposits as evidence of aqueous alteration on (1) Ceres. Nature. 29 June 2016, s. 54–57. Dostupné online [cit. 2016-06-30]. DOI 10.1038/nature18290. PMID 27362221.

- ↑ Dawn data from Ceres publicly released: Finally, color global portraits! [online]. [cit. 2015-11-09]. Dostupné online.

- ↑ Dawn discovers evidence for organic material on Ceres (Update) [online]. 16 February 2017 [cit. 2017-02-17]. Dostupné online.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i Chybná citace: Chyba v tagu

<ref>; citaci označenéhoskinnení určen žádný text - ↑ a b c HOGG, Helen Sawyer. The Titius-Bode Law and the Discovery of Ceres. Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada. 1948, s. 241–246. Bibcode 1948JRASC..42..241S.

- ↑ HOSKIN, Michael. The Cambridge Concise History of Astronomy. [s.l.]: Cambridge University press, 1999. ISBN 978-0-521-57600-0. S. 160–161.

- ↑ LANDAU, Elizabeth. Ceres: Keeping Well-Guarded Secrets for 215 Years [online]. 26 January 2016 [cit. 2016-01-26]. Dostupné online.

- ↑ a b c d e f g FORBES, Eric G. Gauss and the Discovery of Ceres. Journal for the History of Astronomy. 1971, s. 195–199. Bibcode 1971JHA.....2..195F.

- ↑ CUNNINGHAM, Clifford J. The first asteroid: Ceres, 1801–2001. [s.l.]: Star Lab Press, 2001. Dostupné online. ISBN 978-0-9708162-1-4.

- ↑ HILTON, James L. Asteroid Masses and Densities [online]. [cit. 2008-06-23]. Dostupné online.

- ↑ HUGHES, D. W. The Historical Unravelling of the Diameters of the First Four Asteroids. R.A.S. Quarterly Journal. 1994, s. 331. Bibcode 1994QJRAS..35..331H.(Page 335)

- ↑ Foderà Serio, G.; MANARA, A.; SICOLI, P. Asteroids III. Redakce W. F. Bottke Jr.. Tucson, Arizona: University of Arizona Press, 2002. Dostupné online. Kapitola Giuseppe Piazzi and the Discovery of Ceres, s. 17–24.

- ↑ Unicode value U+26B3

- ↑ GOULD, B. A. On the symbolic notation of the asteroids. Astronomical Journal. 1852, s. 80. DOI 10.1086/100212. Bibcode 1852AJ......2...80G.

- ↑ Amalgamator Features 2003: 200 Years Ago [online]. 30 October 2003 [cit. 2006-08-21]. Dostupné v archivu pořízeném z originálu dne 7 February 2006.

- ↑ a b c HILTON, James L. When Did the Asteroids Become Minor Planets? [online]. 17 September 2001 [cit. 2006-08-16]. Dostupné v archivu pořízeném z originálu dne 18 January 2010.

- ↑ BATTERSBY, Stephen. Planet debate: Proposed new definitions [online]. New Scientist, 16 August 2006 [cit. 2007-04-27]. Dostupné v archivu pořízeném z originálu dne 5 October 2011.

- ↑ CONNOR, Steve. Solar system to welcome three new planets. www.nzherald.co.nz. NZ Herald, 16 August 2006. Dostupné v archivu pořízeném z originálu dne 5 October 2011.

- ↑ GINGERICH, Owen. The IAU draft definition of "Planet" and "Plutons" [online]. IAU, 16 August 2006 [cit. 2007-04-27]. Dostupné v archivu pořízeném z originálu dne 5 October 2011.

- ↑ The IAU Draft Definition of Planets And Plutons [online]. SpaceDaily, 16 August 2006 [cit. 2007-04-27]. Dostupné v archivu pořízeném z originálu dne 18 January 2010.

- ↑ a b c d e f RIVKIN, A. S.; VOLQUARDSEN, E. L.; CLARK, B. E. The surface composition of Ceres:Discovery of carbonates and iron-rich clays. Icarus. 2006, s. 563–567. Dostupné online [cit. 8 December 2007]. DOI 10.1016/j.icarus.2006.08.022. Bibcode 2006Icar..185..563R.

- ↑ Gaherty, Geoff; "How to Spot Giant Asteroid Vesta in Night Sky This Week", 3 August 2011 How to Spot Giant Asteroid Vesta in Night Sky This Week | Asteroid Vesta Skywatching Tips | Amateur Astronomy, Asteroids & Comets | Space.com October 2011/http://www.webcitation.org/62D6DYR28?url=http://www.space.com/12537-asteroid-vesta-skywatching-tips.html Archivováno 5. 10. 2011 na Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Question and answers 2 [online]. IAU [cit. 2008-01-31]. Dostupné v archivu pořízeném z originálu dne 5 October 2011.

- ↑ SPAHR, T. B. MPEC 2006-R19: EDITORIAL NOTICE [online]. Minor Planet Center, 7 September 2006 [cit. 2008-01-31]. Dostupné v archivu pořízeném z originálu dne 5 October 2011.

- ↑ LANG, Kenneth. The Cambridge Guide to the Solar System. [s.l.]: Cambridge University Press, 2011. Dostupné online. S. 372, 442.

- ↑ NASA/JPL, Dawn Views Vesta, 2 August 2011 October 2011/http://www.webcitation.org/62D6G0qTd?url=http://www.ustream.tv/recorded/16375687/highlight/191666 Archivováno 5. 10. 2011 na Wayback Machine. ("Dawn will orbit two of the largest asteroids in the Main Belt").

- ↑ DE PATER; LISSAUER. Planetary Sciences. 2nd. vyd. [s.l.]: Cambridge University Press, 2010. ISBN 978-0-521-85371-2.

- ↑ MANN, Ingrid; NAKAMURA, Akiko; MUKAI, Tadashi. Small bodies in planetary systems. [s.l.]: Springer-Verlag, 2009. (Lecture Notes in Physics; sv. 758). ISBN 978-3-540-76934-7.

- ↑ Chybná citace: Chyba v tagu

<ref>; citaci označenéCeres-POEnení určen žádný text - ↑ a b c Chybná citace: Chyba v tagu

<ref>; citaci označenéjpl_sbdbnení určen žádný text - ↑ a b Cellino, A. Asteroids III. [s.l.]: University of Arizona Press, 2002. Dostupné online. Bibcode 2002aste.conf..633C. Kapitola Spectroscopic Properties of Asteroid Families, s. 633–643 (Table on p. 636).

- ↑ Kelley, M. S.; GAFFEY, M. J. A Genetic Study of the Ceres (Williams #67) Asteroid Family. Bulletin of the American Astronomical Society. 1996, s. 1097. Bibcode 1996BAAS...28R1097K.

- ↑ KOVAČEVIĆ, A. B. Determination of the mass of Ceres based on the most gravitationally efficient close encounters. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 2011, s. 2725–2736. DOI 10.1111/j.1365-2966.2011.19919.x. Bibcode 2012MNRAS.419.2725K. arXiv 1109.6455.

- ↑ CHRISTOU, A. A. Co-orbital objects in the main asteroid belt. Astronomy and Astrophysics. 2000, s. L71–L74. Bibcode 2000A&A...356L..71C.

- ↑ CHRISTOU, A. A.; WIEGERT, P. A population of Main Belt Asteroids co-orbiting with Ceres and Vesta. Icarus. January 2012, s. 27–42. ISSN 0019-1035. DOI 10.1016/j.icarus.2011.10.016. Bibcode 2012Icar..217...27C. arXiv 1110.4810.

- ↑ Solex numbers generated by Solex [online]. [cit. 2009-03-03]. Dostupné v archivu pořízeném z originálu dne 29 April 2009.

- ↑ Williams, David R. Asteroid Fact Sheet. nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov. 2004. Dostupné v archivu pořízeném z originálu dne 18 January 2010.

- ↑ SCHORGHOFER, N.; MAZARICO, E.; PLATZ, T.; PREUSKER, F.; SCHRÖDER, S. E.; RAYMOND, C. A.; RUSSELL, C. T. The permanently shadowed regions of dwarf planet Ceres. Geophysical Research Letters. 6 July 2016, s. 6783–6789. DOI 10.1002/2016GL069368. Bibcode 2016GeoRL..43.6783S.

- ↑ RAYMAN, Marc D. Dawn Journal, May 28, 2015 [online]. Jet Propulsion Laboratory, 28 May 2015 [cit. 2015-05-29]. Dostupné online.

- ↑ PITJEVA, E. V. High-Precision Ephemerides of Planets—EPM and Determination of Some Astronomical Constants. Solar System Research. 2005, s. 176–186. DOI 10.1007/s11208-005-0033-2. Bibcode 2005SoSyR..39..176P.

- ↑ a b c d THOMAS, P. C.; PARKER, J. WM.; MCFADDEN, L. A. Differentiation of the asteroid Ceres as revealed by its shape. Nature. 2005, s. 224–226. DOI 10.1038/nature03938. PMID 16148926. Bibcode 2005Natur.437..224T.

- ↑ Approximately forty percent that of Australia, a third the size of the US or Canada, 12× that of the UK

- ↑ a b c PARKER, J. W.; STERN, ALAN S.; THOMAS PETER C. Analysis of the first disk-resolved images of Ceres from ultraviolet observations with the Hubble Space Telescope. The Astronomical Journal. 2002, s. 549–557. DOI 10.1086/338093. Bibcode 2002AJ....123..549P. arXiv astro-ph/0110258.

- ↑ SAINT-PÉ, O.; COMBES, N.; RIGAUT F. Ceres surface properties by high-resolution imaging from Earth. Icarus. 1993, s. 271–281. DOI 10.1006/icar.1993.1125. Bibcode 1993Icar..105..271S.

- ↑ Sulfur, Sulfur Dioxide, Graphitized Carbon Observed on Ceres [online]. spaceref.com, 3 September 2016 [cit. 2016-09-08]. Dostupné online.

- ↑ a b c d e CARRY, Benoit. Near-Infrared Mapping and Physical Properties of the Dwarf-Planet Ceres. Astronomy & Astrophysics. 2007, s. 235–244. Dostupné v archivu pořízeném z originálu dne 30 May 2008. DOI 10.1051/0004-6361:20078166. Bibcode 2008A&A...478..235C. arXiv 0711.1152.

- ↑ a b c Keck Adaptive Optics Images the Dwarf Planet Ceres [online]. Adaptive Optics, 11 October 2006 [cit. 2007-04-27]. Dostupné v archivu pořízeném z originálu dne 18 January 2010.

- ↑ a b c d e f LI, Jian-Yang; MCFADDEN, LUCY A.; PARKER, JOEL WM. Photometric analysis of 1 Ceres and surface mapping from HST observations. Icarus. 2006, s. 143–160. Dostupné online [cit. 8 December 2007]. DOI 10.1016/j.icarus.2005.12.012. Bibcode 2006Icar..182..143L.

- ↑ a b Largest Asteroid May Be 'Mini Planet' with Water Ice. hubblesite.org. HubbleSite, 7 September 2005. Dostupné v archivu pořízeném z originálu dne 5 October 2011.

- ↑ Arizona State University. The case of the missing craters [online]. 26 July 2016 [cit. 2017-03-08]. Dostupné online.

- ↑ MARCHI, S.; ERMAKOV, A. I.; RAYMOND, C. A.; FU, R. R.; O’BRIEN, D. P.; BLAND, M. T.; AMMANNITO, E. The missing large impact craters on Ceres. Nature Communications. 26 July 2016, s. 12257. DOI 10.1038/ncomms12257. Bibcode 2016NatCo...712257M.

- ↑ News – Ceres Spots Continue to Mystify in Latest Dawn Images [online]. Dostupné online.

- ↑ STEIGERWALD, Bill. NASA Discovers "Lonely Mountain" on Ceres Likely a Salty-Mud Cryovolcano [online]. NASA, 2 September 2016 [cit. 2017-03-08]. Dostupné online.

- ↑ Ceres: The tiny world where volcanoes erupt ice. SpaceDaily. 5 September 2016. Dostupné online [cit. 8 March 2017].

- ↑ SORI, Michael M.; BYRNE, Shane; BLAND, Michael T.; BRAMSON, Ali M.; ERMAKOV, Anton I.; HAMILTON, Christopher W.; OTTO, Katharina A. The vanishing cryovolcanoes of Ceres. Geophysical Research Letters. 2017. DOI 10.1002/2016GL072319.

- ↑ USGS: Ceres nomenclature [online]. [cit. 2015-07-16]. Dostupné online.

- ↑ Šablona:Cite speech

- ↑ LANDAU, Elizabeth. Ceres Animation Showcases Bright Spots [online]. NASA, 11 May 2015 [cit. 2015-05-13]. Dostupné online.

- ↑ a b WITZE, Alexandra. Mystery haze appears above Ceres’s bright spots. Nature News. 21 July 2015. Dostupné online [cit. 23 July 2015]. DOI 10.1038/nature.2015.18032.

- ↑ RIVKIN, Andrew. Dawn at Ceres: A haze in Occator crater? [online]. The Planetary Society, 21 July 2015 [cit. 2017-03-08]. Dostupné online.

- ↑ Dawn Mission – News – Detail [online]. NASA. Dostupné online.

- ↑ REDD, Nola Taylor. Water Ice on Ceres Boosts Hopes for Buried Ocean [Video] [online]. [cit. 2016-04-07]. Dostupné online.

- ↑ PIA20348: Ahuna Mons Seen from LAMO [online]. Jet Propulsion Lab, 7 March 2016 [cit. 2016-04-14]. Dostupné online.

- ↑ 0.72–0.77 anhydrous rock by mass, per McKinnon, William B.; (2008) "On the Possibility of Large KBOs Being Injected Into the Outer Asteroid Belt". American Astronomical Society, DPS meeting No. 40, #38.03 October 2011/http://www.webcitation.org/62D6Hmyrx?url=http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2008DPS....40.3803M Archivováno 5. 10. 2011 na Wayback Machine.

- ↑ CAREY, Bjorn. Largest Asteroid Might Contain More Fresh Water than Earth. space.com. SPACE.com, 7 September 2005. Dostupné v archivu pořízeném z originálu dne 5 October 2011.

- ↑ DPS 2015: First reconnaissance of Ceres by Dawn [online]. Dostupné online.

- ↑ What's Inside Ceres? New Findings from Gravity Data [online]. Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Dostupné online.

- ↑ a b PARK, R. S.; KONOPLIV, A. S.; BILLS, B. G.; RAMBAUX, N.; CASTILLO-ROGEZ, J. C.; RAYMOND, C. A.; VAUGHAN, A. T. A partially differentiated interior for (1) Ceres deduced from its gravity field and shape. Nature. 2016-08-03, s. 515–517. DOI 10.1038/nature18955. PMID 27487219.

- ↑ THOMAS, P. C. Sizes, shapes, and derived properties of the saturnian satellites after the Cassini nominal mission. Icarus. July 2010, s. 395–401. Dostupné online. DOI 10.1016/j.icarus.2010.01.025. Bibcode 2010Icar..208..395T.

- ↑ NEUMANN, W.; BREUER, D.; SPOHN, T. Modelling the internal structure of Ceres: Coupling of accretion with compaction by creep and implications for the water-rock differentiation. Astronomy & Astrophysics. 2015-12-02, s. A117. Dostupné online. DOI 10.1051/0004-6361/201527083. Bibcode 2015A&A...584A.117N.

- ↑ a b A'HEARN, Michael F.; FELDMAN, PAUL D. Water vaporization on Ceres. Icarus. 1992, s. 54–60. DOI 10.1016/0019-1035(92)90206-M. Bibcode 1992Icar...98...54A.

- ↑ Ceres: The Smallest and Closest Dwarf Planet. Space.com 22 January 2014

- ↑ Dwarf Planet Ceres, Artist's Impression. 21 January 2014. NASA

- ↑ Jewitt, D; CHIZMADIA, L.; GRIMM, R.; PRIALNIK, D. Protostars and Planets V. Redakce Reipurth, B.; Jewitt, D.; Keil, K.. [s.l.]: University of Arizona Press, 2007. Dostupné online. ISBN 0-8165-2654-0. Kapitola Water in the Small Bodies of the Solar System, s. 863–878.

- ↑ a b c KÜPPERS, M.; O'ROURKE, L.; BOCKELÉE-MORVAN, D.; ZAKHAROV, V.; LEE, S.; VON ALLMEN, P.; CARRY, B. Localized sources of water vapour on the dwarf planet (1) Ceres. Nature. 23 January 2014, s. 525–527. ISSN 0028-0836. DOI 10.1038/nature12918. PMID 24451541. Bibcode 2014Natur.505..525K.

- ↑ CAMPINS, H.; COMFORT, C. M. Solar system: Evaporating asteroid. Nature. 23 January 2014, s. 487–488. DOI 10.1038/505487a. PMID 24451536. Bibcode 2014Natur.505..487C.

- ↑ HANSEN, C. J.; ESPOSITO, L.; STEWART, A. I.; COLWELL, J.; HENDRIX, A.; PRYOR, W.; SHEMANSKY, D. Enceladus' Water Vapor Plume. Science. 2006-03-10, s. 1422–1425. DOI 10.1126/science.1121254. PMID 16527971. Bibcode 2006Sci...311.1422H.

- ↑ ROTH, L.; SAUR, J.; RETHERFORD, K. D.; STROBEL, D. F.; FELDMAN, P. D.; MCGRATH, M. A.; NIMMO, F. Transient Water Vapor at Europa's South Pole. Science. 26 November 2013, s. 171–174. Dostupné online [cit. 26 January 2014]. DOI 10.1126/science.1247051. PMID 24336567. Bibcode 2014Sci...343..171R.

- ↑ Arizona State University. Ceres: The tiny world where volcanoes erupt ice [online]. 1 September 2016 [cit. 2017-03-08]. Dostupné online.

- ↑ HIESINGER, H.; MARCHI, S.; SCHMEDEMANN, N.; SCHENK, P.; PASCKERT, J. H.; NEESEMANN, A.; OBRIEN, D. P. Cratering on Ceres: Implications for its crust and evolution. Science. 1 September 2016, s. aaf4759. DOI 10.1126/science.aaf4759. Bibcode 2016Sci...353.4759H.

- ↑ NASA/Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Ceres' geological activity, ice revealed in new research [online]. 1 September 2016 [cit. 2017-03-08]. Dostupné online.

- ↑ Confirmed: Ceres Has a Transient Atmosphere - Universe Today. Universe Today. 2017-04-06. Dostupné online [cit. 2017-04-14]. (anglicky)

- ↑ PETIT, Jean-Marc; MORBIDELLI, ALESSANDRO. The Primordial Excitation and Clearing of the Asteroid Belt. Icarus. 2001, s. 338–347. Dostupné online [cit. 25 June 2009]. DOI 10.1006/icar.2001.6702. Bibcode 2001Icar..153..338P.

- ↑ Approximately a 10% chance of the asteroid belt acquiring a Ceres-mass KBO. McKinnon, William B.; (2008) "On the Possibility of Large KBOs Being Injected Into the Outer Asteroid Belt". American Astronomical Society, DPS meeting No. 40, #38.03 October 2011/http://www.webcitation.org/62D6Hmyrx?url=http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2008DPS....40.3803M Archivováno 5. 10. 2011 na Wayback Machine.

- ↑ GREICIUS, Tony. Recent Hydrothermal Activity May Explain Ceres' Brightest Area [online]. 29 June 2016. Dostupné online.

- ↑ THOMAS, Peter C.; BINZEL, RICHARD P.; GAFFEY, MICHAEL J. Impact Excavation on Asteroid 4 Vesta: Hubble Space Telescope Results. Science. 1997, s. 1492–1495. DOI 10.1126/science.277.5331.1492. Bibcode 1997Sci...277.1492T.

- ↑ WALL, Mike. NASA's Dawn Mission Spies Ice Volcanoes on Ceres [online]. 2 September 2016 [cit. 2017-03-08]. Dostupné online.

- ↑ a b CASTILLO-ROGEZ, J. C.; MCCORD, T. B.; AND DAVIS, A. G. Ceres: evolution and present state. Lunar and Planetary Science. 2007, s. 2006–2007. Dostupné online [cit. 25 June 2009].

- ↑ WALL, Mike. Strange Bright Spots on Ceres Create Mini-Atmosphere on Dwarf Planet. Space.com. 27 July 2014. Dostupné online [cit. 2015-08-03].

- ↑ Catling, David C. Astrobiology: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013. ISBN 0-19-958645-4. S. 99.

- ↑ Castillo-Rogez, J. C. (2010). "Habitability Potential of Ceres, a Warm Icy Body in the Asteroid Belt" in LPI Conference 2010., Lunar and Planetary Institute.

- ↑ HAND, Eric. Dawn probe to look for a habitable ocean on Ceres. Science. 20 February 2015, s. 813–814. Dostupné online [cit. 2015-09-16]. DOI 10.1126/science.347.6224.813. PMID 25700494. Bibcode 2015Sci...347..813H.

- ↑ Houtkooper, Joop M.; "Glaciopanspermia: Seeding the Terrestrial Planets with Life?" Institute for Psychobiology and Behavioral Medicine, Justus-Liebig-University, Giessen, Germany

- ↑ O'Neill, Ian. Life on Ceres: Could the Dwarf Planet be the Root of Panspermia [online]. 5 March 2009 [cit. 2012-01-30]. Dostupné online.

- ↑ SPHERE Maps the Surface of Ceres [online]. [cit. 2015-09-08]. Dostupné online.

- ↑ Menzel, Donald H.; PASACHOFF, JAY M. A Field Guide to the Stars and Planets. 2nd. vyd. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin, 1983. ISBN 978-0-395-34835-2. S. 391.

- ↑ Martinez, Patrick, The Observer's Guide to Astronomy, page 298. Published 1994 by Cambridge University Press

- ↑ MILLIS, L. R.; WASSERMAN, L. H.; FRANZ, O. Z. The size, shape, density, and albedo of Ceres from its occultation of BD+8°471. Icarus. 1987, s. 507–518. DOI 10.1016/0019-1035(87)90048-0. Bibcode 1987Icar...72..507M.

- ↑ Observations reveal curiosities on the surface of asteroid Ceres [online]. [cit. 2006-08-16]. Dostupné v archivu pořízeném z originálu dne 5 October 2011.

- ↑ a b Asteroid Occultation Updates [online]. Asteroidoccultation.com, 22 December 2012 [cit. 2013-08-20]. Dostupné v archivu pořízeném z originálu dne 2012-07-12.

- ↑ Water Detected on Dwarf Planet Ceres [online]. Science.nasa.gov [cit. 2014-01-24]. Dostupné online.

- ↑ Ulivi, Paolo; HARLAND, DAVID. Robotic Exploration of the Solar System: Hiatus and Renewal, 1983–1996. [s.l.]: Springer, 2008. (Springer Praxis Books in Space Exploration). ISBN 0-387-78904-9. S. 117–125.

- ↑ RUSSELL, C. T.; CAPACCIONI, F.; CORADINI, A. Dawn Mission to Vesta and Ceres. Earth, Moon, and Planets. October 2007, s. 65–91. Dostupné online [cit. 13 June 2011]. DOI 10.1007/s11038-007-9151-9. Bibcode 2007EM&P..101...65R.

- ↑ Cook, Jia-Rui C.; BROWN, DWAYNE C. NASA's Dawn Captures First Image of Nearing Asteroid [online]. NASA/JPL, 11 May 2011 [cit. 2011-05-14]. Dostupné online.

- ↑ SCHENK, P. Year of the 'Dwarves': Ceres and Pluto Get Their Due [online]. Planetary Society, 15 January 2015 [cit. 2015-02-10]. Dostupné online.

- ↑ RAYMAN, Marc. Dawn Journal: Looking Ahead at Ceres [online]. Planetary Society, 1 December 2014 [cit. 2015-03-02]. Dostupné online.

- ↑ RAYMAN, Marc. Dawn Journal: Maneuvering Around Ceres [online]. Planetary Society, 3 March 2014 [cit. 2015-03-06]. Dostupné online.

- ↑ RAYMAN, Marc. Dawn Journal: Explaining Orbit Insertion [online]. Planetary Society, 30 April 2014 [cit. 2015-03-06]. Dostupné online.

- ↑ RAYMAN, Marc. Dawn Journal: HAMO at Ceres [online]. Planetary Society, 30 June 2014 [cit. 2015-03-06]. Dostupné online.

- ↑ RAYMAN, Marc. Dawn Journal: From HAMO to LAMO and Beyond [online]. Planetary Society, 31 August 2014 [cit. 2015-03-06]. Dostupné online.

- ↑ RUSSEL, C. T.; CAPACCIONI, F.; CORADINI, A. Dawn Discovery mission to Vesta and Ceres: Present status. Advances in Space Research. 2006, s. 2043–2048. DOI 10.1016/j.asr.2004.12.041. Bibcode 2006AdSpR..38.2043R.

- ↑ RAYMAN, Marc. Dawn Journal: Closing in on Ceres [online]. Planetary Society, 30 January 2015 [cit. 2015-03-02]. Dostupné online.

- ↑ Dawn Operating Normally After Safe Mode Triggered [online]. NASA/JPL, 16 September 2014 [cit. 2015-03-18]. Dostupné v archivu pořízeném z originálu dne 25 December 2014.

- ↑ China's Deep-space Exploration to 2030 by Zou Yongliao Li Wei Ouyang Ziyuan Key Laboratory of Lunar and Deep Space Exploration, National Astronomical Observatories, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing

- ↑ Staff. First 17 Names Approved for Features on Ceres [online]. 17 July 2015 [cit. 2015-08-09]. Dostupné online.

References editovat

Odkazy editovat

Související články editovat

Reference editovat

Literatura editovat

Externí odkazy editovat

- Obrázky, zvuky či videa k tématu Chmee2/Pískoviště na Wikimedia Commons

- Encyklopedické heslo Ceres v Ottově slovníku naučném ve Wikizdrojích

- TICHÁ, Jana. (Ne)zapomenout na Palermo. IAN, 2001

- Movie of one Cererian rotation (processed Hubble images) (angl.)

- Informationen zum Aufbau (2005) (něm.)

- HST 2001. SwRI (angl.)

- HST Pictures 2003-2004. STScI (angl.)

- (1) Ceres. NASA-JPL (angl., graf dráhy)

- Heavens Above (česky, hvězdná mapka k vyhledání)

- (1) Ceres. AstDys (angl., elementy dráhy a další data)

- astronomy.com, movie credit J. Parker, Southwest Research Institute. (angl.)

Popis objektu editovat

I když je Ceres největším tělesem v hlavním pásu planetek a její albedo patří k průměru (0,113), není ani při optimální opozici, kdy se přibližuje k Zemi na 1,59 AU prakticky pozorovatelná pouhým okem. Maximální zdánlivá hvězdná velikost totiž dosahuje nejvýše hodnoty 7,0m; teoreticky by tato hodnota sice za velice příznivých pozorovacích podmínek u lidí s mimořádně citlivým zrakem stačila ke spatření Cerery, ale takové pozorování zatím nebylo nikdy potvrzeno. Stačí však i malý dalekohled, případně triedr, aby mohla být pozorována, ovšem pouze jako jasný bod, podobný hvězdě.

Relativně velká vzdálenost je také na překážku bližšímu zkoumání tohoto tělesa.

Vzhled objektu editovat

Pozorování Hubbleovým kosmickým dalekohledem (HST) i pomocí nejvýkonnějších pozemských dalekohledů ukázalo, že Ceres má téměř kulový tvar, s mírným polárním zploštěním. Je to v souladu s předpokladem, že jeho gravitační přitažlivost umožnila dosáhnout isostáze, tedy zaujmutí tvaru s minimální gravitační energií. Vedle planetky (4) Vesta a možná i planetky (10) Hygiea je tedy jediným objektem v pásu planetek, u kterého k tomuto procesu došlo.

Na povrchu byla na snímcích pořízených 1995 s malým rozlišením asi 60 km/px v ultrafialové části spektra pomocí HST objevena tmavší oblast, o rozměrech přibližně 250 km, která byla nazvána na počest objevitele planetky Piazzi a o níž se předpokládalo, že by to mohl být impaktní kráter. Při pozdější pozorováních v roce 2002 s podobným rozlišením Keckovým dalekohledem na Havajských ostrovech ve viditelné oblasti s použitím adaptivní optiky, však nebyl Piazzi pozorován. Místo něj byly spatřeny dvě jiné tmavé oblasti, z nich jedna měla středové zjasnění. O nich se také předpokládá, že se jedná o krátery. Pozorování pomocí HST s vyšším rozlišením 30 km/px v létech 2003 a 2004 ve viditelném světle odhalilo další albedový útvar, tentokráte s vyšším albedem a tedy světlejší, o průměru asi 40 km, jehož podstata je dosud neznámá.

Příbuznost s jinými planetkami editovat

V minulosti se předpokládalo, že Ceres je mateřským tělesem rodiny těles nazývané jejím jménem. Nejnovější výpočty dlouhodobého vývoje dráhy však ukazují, že sama Cerera do této oblasti připutovala, podle jedné z teorií z Kuiperova pásu [1] a že tedy nemá s ostatními tělesy žádnou spojitost. Také neexistence náznaků na Cereře o velkém impaktu, který by vedl ke vzniku sekundárních těles, snižuje pravděpodobnost případné příbuznosti dalších planetek s Cererou.

Původ jména editovat

Piazzi nazval objevený objekt Ceres Ferdinandea. První část jména pochází od římské bohyně Ceres, která byla ochránkyní zemědělců a úrody, současně patronkou ostrova Sicílie a sestrou Jupitera; druhá část jména byla přidána na počest Piazziho královského ochránce a sponzora, Ferdinanda IV. Protože použití tohoto přídomku nebylo v jiných zemích z politických důvodů příliš vítáno, velice brzy z názvu tohoto objektu zmizelo.

V Německu J. E. Bode navrhoval pro toto těleso jméno Juno (později použité pro třetí objevenou planetku (3) Juno). Krátce se používalo též jméno Hera (později tento název dostala planetka (103) Hera).

Průzkum objektu editovat

První sondou, která prozkoumala Ceres, byla sonda Dawn. Ta odstartovala v září 2007, v letech 2011 a 2012 obíhala planetku (4) Vesta a na oběžné dráze Ceres je od března 2015.[1]

Chybná citace: Nalezena značka <ref> pro skupinu „lower-alpha“, ale neexistuje příslušná značka <references group="lower-alpha"/>

Chybná citace: Nalezena značka <ref> pro skupinu „pozn.“, ale neexistuje příslušná značka <references group="pozn."/>

- ↑ ČTK. Lidstvo poprvé „zaparkovalo“ u trpasličí planety. A hned u té nejtajemnější [online]. Technet.cz, 2015-03-09 [cit. 2015-03-10]. Dostupné online.